Iconographic Fusion in Caravaggio’s Amor Vincit Omnia: Cupid as a Hybrid of Ganymede and Jupiter : excerpt from seminar paper

Bar Plivazky | Admonitbar@gmail.com

Iconographic Fusion in Caravaggio’s Amor Vincit Omnia: Cupid as a Hybrid of

Ganymede and Jupiter

The Open University of Israel

Excerpt from seminar paper, The Open University of Israel, “The Classical in Art: From

Greece to the Present” (Course 10999, 2025)

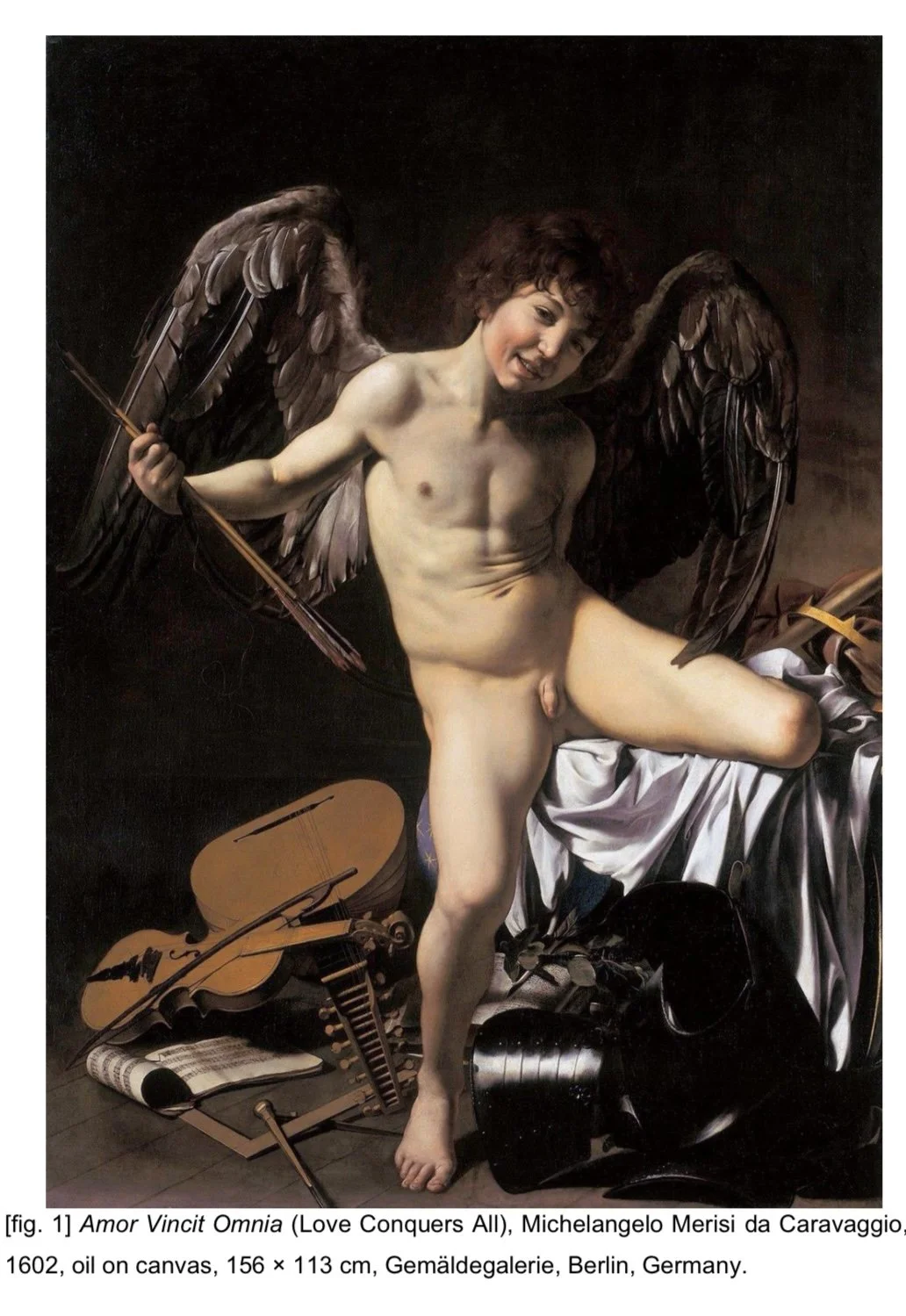

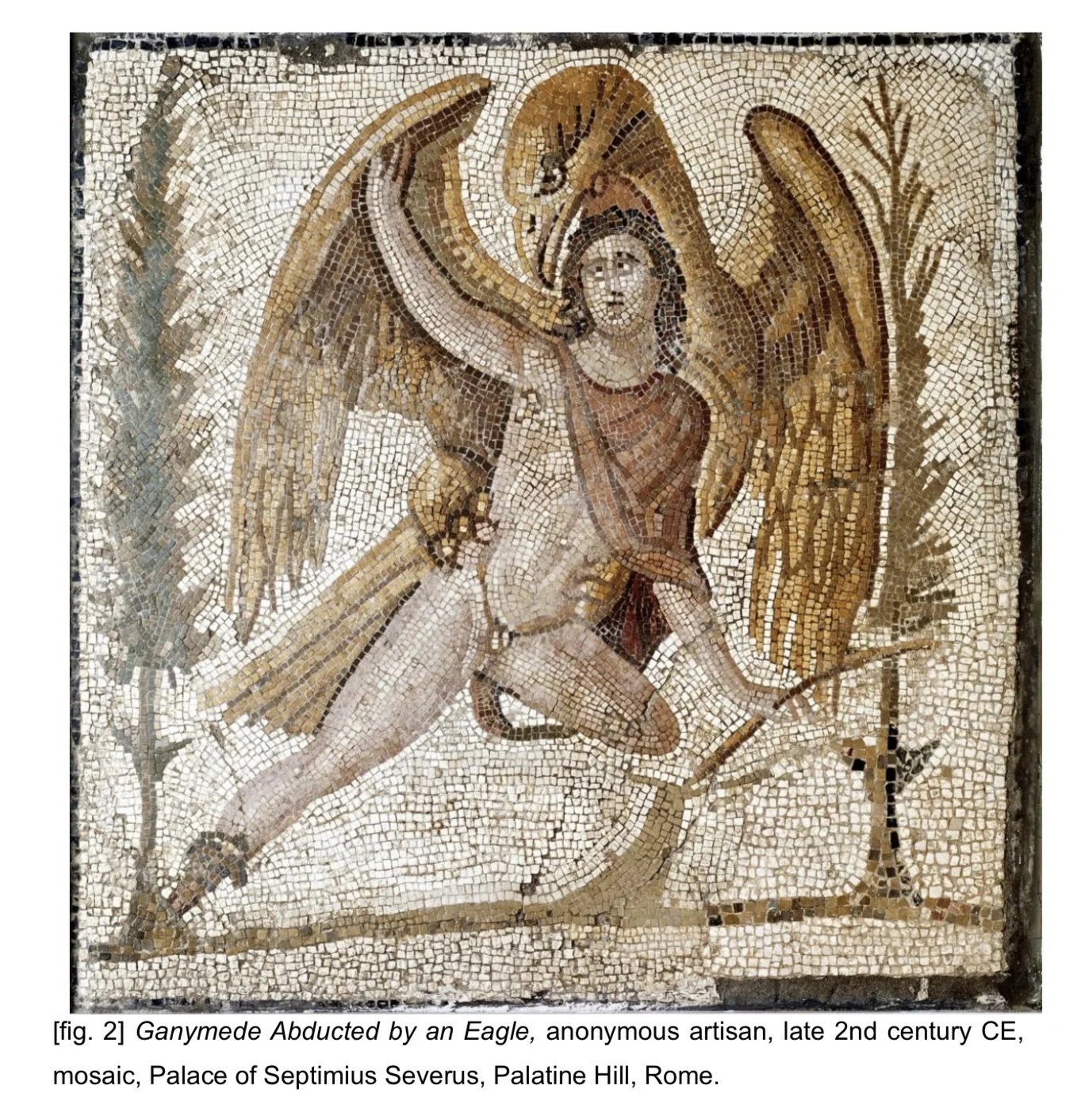

In my seminar paper, I examined the premise that the depiction of Cupid in Amor Vincit

Omnia [fig. 1], painted by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio in 1602 for his patron

Vincenzo Giustiniani, is grounded in ancient Roman representations of the youth

Ganymede. Caravaggio employed a classicizing quotation but reconfigured its

meaning for his early seventeenth-century cultural world. In this work, Cupid appears

in Ganymede’s traditional pose, one leg bent while the other is extended, referencing

Ganymede’s ascent to the heavens, borne by Jupiter in the guise of an eagle [figs. 2–

3].1

To analyze the painting, I surveyed literary and visual representations of Ganymede

and Cupid in primary sources and scholarly literature. I examined the figures involved,

whether mythological or biographical, through the biographies of artists and patrons,

poetry and correspondence, legal sources, and selected works of art from ancient

Rome through the Baroque period.

Seeking to reconstruct period-appropriate modes of thought, I followed the

iconographic tradition of which Caravaggio himself would have been a student, and

considered the contemporary reception of his work. I reviewed Renaissance sexuality

and examined attitudes toward representations of Ganymede amid late Renaissance

displays. I also addressed the use of allegory as a means of concealment in

Caravaggio’s other paintings. To avoid anachronistic impositions, I emphasized

historical and sociological context, and I barely assigned interpretive weight to

contemporary gender theory.2

1 Hellmut Sichtermann, Ganymed: Mythos und Gestalt in der antiken Kunst (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1955),

66.

2 Helen Langdon, Caravaggio and Cupid: Homage and Rivalry in Rome and Florence (London,

National Gallery Publications, 1998), 18.

Ganymede in the Renaissance: between Michelangelo and Cellini

I illustrate Renaissance representations of Ganymede through two poles: Michelangelo as a

High Renaissance point of departure and Benvenuto Cellini as a later sixteenth-century pole.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) witnessed the shift from Reformation to

Counter-Reformation values, manifested in art by a move away from the pursuit of

Neoplatonic ideals to demands for moral purity and repression of desire.3 In The Rape

of Ganymede [fig. 4], Ganymede’s conventional pose signals Michelangelo’s classical

learning.4 He gifted this drawing to Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, whom he compared to

Ganymede in his poetry. 5 Barkan argues that Ganymede poses here as

Michelangelo’s self-allegory; a metaphor for his love, his pain, and his fear of

accusation or censorship. The image thus combines transcendent love with anxiety.6

Linking the male figure with the intellect and the divine, the work also draws on the

Neoplatonic Renaissance convention of Ganymede as an emblem of

transcendence.

7 In the sixteenth century, the sculptor Benvenuto Cellini wrote in his

autobiography that art “exalts the god you worship,” noting that “Jove used it with

Ganymede in paradise, and here upon this earth it is practiced by some of the

greatest emperors and kings.”8 Cellini’s remarks expose the double standards of his

time: on the one hand, homoerotic relations were subject to punishment; on the

other, affiliation with high social rank could offer effective protection from

prosecution.9

Although sodomy was considered a sin throughout the Middle Ages and the

Renaissance, from the mid-sixteenth century onward, same-sex acts increasingly

became a serious crime. It faced increased moral vigilance, legislative enforcement,

and artistic censorship. In its session entitled “On Sacred Images,” the Council of Trent

3 James M. Saslow, Ganymede in the Renaissance: Homosexuality in Art and Society (New Haven:

Yale University Press, 1986), 120.

4 Ibid., 38–39.

5 Ibid., 21.

6 Leonard Barkan, Transuming Passion: Ganymede and the Erotics of Humanism (Stanford, CA:

Stanford University Press, 1991), 148.

7 Saslow, Ganymede in the Renaissance, 120.

8 Benvenuto Cellini, The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, trans. George Bull (London: Penguin

Classics, 1998), 324.

9 Jacqueline Murray and Nicholas Terpstra, eds., Sex, Gender and Sexuality in Renaissance Italy

(London and New York: Routledge, 2019), 32.

determined unequivocally that all manifestations of indecency in art should be avoided:

figures were not to be adorned with beauty that aroused desire, nor were any

‘anomalous’ images to be displayed in churches.10 As a result, Renaissance artists

could no longer explicitly represent erotic relations between men without risking severe

consequences.11 Thus, they increasingly used the filter of mythology.

Benvenuto Cellini carved his sensuous Ganymede in 1545, the very year of the

Council of Trent’s first convocation.12 His Ganymede, tenderly caressing the eagle and

offering it a courtship gift, is regarded as the last public Renaissance representation in

Italy to explicitly emphasize the sexual dimension of the myth.13 The limits of visual

legitimacy had been redrawn, boundaries within which Caravaggio would be

compelled to operate some fifty years later.14

In the Renaissance, Ganymede operated in both spiritual registers (Neoplatonism,

Christian alchemy) and cultural ones, and as a format for the discussion of desire and

social boundaries.

Together, these points suggest that Caravaggio may have yearned to continue the

Ganymedean tradition to encompass all these meanings and questions, including the erotic

ones. Due to censorship, he could not openly depict Ganymede, so, through classicizing

quotation, he could depict Cupid in a Ganymede-like pose to signal these at the Giustiniani

palace, hinting, for those who knew where to look, at the bond between Jupiter and

Ganymede.

10 Saslow, Ganymede in the Renaissance, 61.

11 Ibid., 47.

12 Ibid., 198.

13 Ibid., 198.

14 Ibid., 201.

Homoerotic Reading in Caravaggio’s Oeuvre

Although no conclusive evidence survives regarding the sexual orientation of either

the patron Vincenzo Giustiniani or Caravaggio himself, the bold and suggestive

sexuality of Caravaggio’s imagery, combined with its striking naturalism, has led

scholars to argue that his work projects his own sensitivities and lived experience onto

the pictorial field.15

Unlike many Renaissance artists, Caravaggio painted living bodies rather than

idealized models; his naturalism, shaped by the antique, produces a remarkably direct

homoerotic gaze that contemporaries noticed and criticized.16

The Church’s rejection of The Inspiration of Saint Matthew shows their concern about

these aspects and supports the argument for the presence of sexual themes in

Caravaggio’s paintings. This experience may have taught him to be more careful in

hiding his messages.17

Caravaggio’s art transcends the boundaries of Counter-Reformation religious painting

and offers his personal response to the mysteries of Christianity. In his public

commissions, he negotiates the integration of intellectual, critical, and personal

perspectives with the demands imposed by the Church. At times, he incorporates self-

portraiture. This fact, among others, accentuates the autobiographical connection

between his work and the experiences of his life.18

Saint Francis in Ecstasy, for example, gestures toward a Neoplatonic homoerotic

connotation. The two men occupy a pose reserved in other paintings for heterosexual

relationships, such as Venus and Adonis. Their naturalism presents corporeality

sharply illuminated and clothed in attire that is overly erotic for a religious image. The

painting includes a partially nude angel. They appear less as narrators of a Christian

15 James M. Saslow, Pictures and Passions: A History of Homosexuality in the Visual Arts (New York:

Viking, 1999), 117.

16 Barkan, Transuming Passion, 91.

17 John T. Spike, ״Saint Matthew and the Angel,״ in Caravaggio, ed. Christopher Lyon (New York and

London: Abbeville Press, 2001), 119.

18 Langdon, Caravaggio: A Life, 218.

story and more as the figures of one man supported in the arms of another within an

intimate physical encounter.

Alongside works such as this one, Amor Vincit Omnia suggests that Caravaggio

operated within an “open homosexual subculture in Rome: sophisticated, self-

confident, and wealthy enough to realize its desires and to develop its own codes and

irony.”20 His work thus articulates a dual visual language, faithful to ecclesiastical

frameworks yet subversive of them. In this language, myth and the classical ideal

function as a veil that enables the expression of non-traditional and personal desire,

either of the patron or artist, defiantly testing the limits of the period.21

19 Ibid., 123.

20 Ibid., 217.

21 Ibid., 218.

Caravaggio and the Antique

In his Lives of the Artists, Baglione recounts an episode in which Caravaggio was

advised to use classical sculptures as models.22 Caravaggio dismissed this advice by

simply gesturing toward a group of bystanders, implying that they would serve as his

models instead. Upon examination of his paintings, it becomes clear that Baglione's

story should not be taken literally. Caravaggio did not rely solely on what he saw in

everyday life; he also drew on ideas from ancient art.23 Caravaggio found much of his

inspiration in the ancient artworks around him in the homes of the Giustiniani and Del

Monte families. Living among their collections, he thought of their classical works in

relation to his own naturalistic style.24

As the public representation of homoeroticism became increasingly restricted, a

private sphere of expression emerged in which artists and patrons alike could

articulate desire while continuing to employ a restrained iconographic code, one

deeply informed by classicism. 25 Caravaggio and his contemporaries employed

quotations from the classical tradition, alla’antica; Greco-Roman art and texts served

to legitimize the aspiration to exalt images of male beauty and eros. Caravaggio

staged his models in tableaux vivants directly derived from Roman sculpture, which at

the time was mistakenly attributed to the great Greek masters.26

In his Ragazzi paintings, young boys are illustrated with garments slipping from their

bodies, exposing flesh as they extend wine or fruit toward the viewer, thereby offering

themselves.27 Some of these figures are likely self-portraits of the artist in his youth,

while others depict entertainers and young servants drawn from the circles of his

patrons. These figures push classical justification to its limits. The androgynous

Musicians [fig. 5] barely maintain the appearance of mythological allegory and more

closely resemble a genre scene depicting half-nude youths, while the figure at the

back right is possibly another self-portrait.28 Here, the mythological serves as a veil for

the depiction of inhabitants of the demi-monde who sold their services to the

aristocracy. Scholars have suggested that such figures were perceived as members

of a semi-clandestine male brotherhood of literary accademie, linked to carnival

22 Avigdor W. G. Poseq, “Caravaggio and the Antique,” Artibus et Historiae 11, no. 21 (1990): 147.

23 Ibid., 148.

24 Langdon, Caravaggio: A Life, 215.

25 Saslow, Pictures and Passions, 116.

26 Langdon, Caravaggio: A Life, 163.

27 Aaron H. De Groft, Caravaggio: Still Life with Fruit on a Stone Ledge (London: Giles, 2006), 67.

28 Saslow, Pictures and Passions, 116.

settings in which men dressed as peasants, sometimes role-played as women, and

composed carival poetry.29 Caravaggio and intellectuals within his circle wrote and

recited such poems within male academies and at carnivals influenced by Roman

festivals. Within these academies, a close affinity emerged between the imitation of

classical paganism and the performance of practices considered morally deviant. As

evidence of this, many members of these circles were accused of sodomy and of

engaging with the “blasphemous and coarse aspects of the classical world.”30

Some of Caravaggio’s paintings were perceived by contemporaries as so ambiguous

that even their identification as religious subjects was not entirely possible. A case in

point is his Saint John the Baptist, which presents a youth sensually entwined with a

ram; when the Giustiniani collection was sold in 1638, the painting was identified not

as a biblical figure but as Corydon, the shepherd from Virgil’s Eclogues.

31 This mistaken identification stemmed from the youth’s classical nudity, which evokes

Greece and Virgilian pastoral tradition, as well as from the fierce naturalism that

conflicts with conventional representations of a holy figure such as John. To this day,

scholarly discussion persists over the subject matter of Caravaggio's other Ragazzi

paintings, densely populated with poses, gestures, white draperies, and musical

instruments drawn from Roman sculpture and literature.32

The absence of Ganymede from Caravaggio's series of mythological youths, despite

the pronounced homoeroticism throughout his oeuvre, raises suspicion of

substitution.33 As I have shown, Ganymede had become so closely associated with

sodomy that his representation was no longer viable for artists wishing to escape these

accusations. Instead, within a framework of classicizing quotation, the charged myth

could be replaced with safer images. Myths and figures from the Greco-Roman world

provided a legitimate iconographic framework through which sexual deviance could

be displaced from the present into a longed-for past, from lived reality into fiction, and

from a restrictive Catholic milieu into the learned gaze of select viewers, thereby

softening the transgression.34

29 De Groft, Caravaggio: Still Life with Fruit, 69.

30 Ibid., 61.

31 ״Caravaggio and the Antique״ ,Poseq, 148–147.

32 De Groft, Caravaggio: Still Life with Fruit, 54.

33 Saslow, Ganymede in the Renaissance, 162.

34 Ibid., 65.

In this context, Amor Vincit Omnia may be read as offering Cupid as a hybrid

representation of Ganymede, encoding a homoerotic reading. 35 This maneuver

reinforces the central claim of this analysis: Caravaggio’s engagement with antiquity

operates as a strategic dialogue capable of embedding Ganymede within Cupid,

thereby masking desire. The absence of Ganymede may thus paradoxically signal his

presence in disguised form, allowing the artist to continue participating in the extensive

tradition of Ganymede representations, now concealed behind the Cupid’s mask.

35 Ibid., 200.

Iconographic Analysis of Amor Vincit Omnia

Caravaggio’s Cupid appears after a long sequence of transformations in Cupid’s

representation, surveyed here from antiquity through the Renaissance and early

Baroque, and at the height of a period saturated with Cupid imagery. Yet his Cupid

stands apart from its precedents through its exceptional iconography. The subject of

the painting is Amor Vincit Omnia, a well-known Virgilian motto from the Eclogues,

frequently depicted in the late sixteenth century.36 Typically, paintings of this title

depict Cupid triumphing over Pan, the god of shepherds, while holding a burning torch.

A contemporary example presents Cupid as an infant trampling intellectual symbols.

It likely served as a partial model for Caravaggio’s composition, yet it differs decisively

in its absence of erotic charge [fig. 6].37

The painting has distinctive iconographic features: Cupid appears alone, without the

multi-figural allegorical orchestra that usually accompanies him. Moreover, unlike most

historical representations, Caravaggio’s Cupid does not wear small white wings but

rather dark, enigmatic eagle wings. He is a youth who confronts the viewer directly,

even brazenly, his posture unashamedly erotic. Reaching his hand behind his body

without an immediately legible justification, he smiles provocatively. Is he hiding

something? His mouth is open as if singing or speaking, evoking theatricality and stage

performance, a motif deeply embedded in Baroque painting. The figure is illuminated

from above, and chiaroscuro heightens the sense of realism. A feather caressing the

thigh directs the viewer’s gaze and activates the senses synaesthetically, while

beneath the bent left leg lies a disordered arrangement of white linens.38

Cupid is shown as victorious and more powerful than all earthly pursuits, a claim

reinforced allegorically by the objects scattered beneath him. As he tramples emblems

of status (crown and laurel wreath), warfare (armor), science (compass, ruler, and

books), and the arts (lute, violin, sheet music, and pen), the painting functions as a

hybrid of still life and vanitas, presenting the “traps of civilization” as subdued by love.39

Documentation of the original viewing conditions strengthens the homoerotic reading.

The painting’s placement behind a curtain, revealed only to a restricted circle of

learned male viewers, suggests that it was intended to convey multiple meanings: a

tribute to elevated classicism and the patron’s erudition, and an object charged with

erotic tension for an audience capable of decoding it.40

36 Ibid., 2.

37 Langdon, Caravaggio and Cupid, 12.

38 Langdon, Caravaggio: A Life, 213.

39 Langdon, Caravaggio and Cupid, 17.

Visual Quotation, Classicism, and Naturalism in Amor Vincit Omnia, In Light of

The Research Question

In Amor Vincit Omnia, classicism functions for Caravaggio as a studied reference and

a contemporary transformation of antiquity. He selects a mythological subject, Cupid,

anchors it in the Virgilian motto Omnia vincit Amor, and stages a living model in a pose

derived from the classical world. The torso recalls the sculpture of Cupid Stringing His

Bow, attributed to Lysippus [fig. 7], a copy of which was present in the Giustiniani

collection. In addition, he may have adopted the leg position associated with ancient

Roman representations of Ganymede, as preserved in Michelangelo’s drawing of

Ganymede in this pose, which was housed in the Del Monte collection Caravaggio

had access to.41

Moreover, classicism in the painting elevates quotation to a form of reanimation,

reviving the ancient image among the original antiquities themselves. Caravaggio’s

Cupid animates the sculpture attributed to Lysippus and in Virgil’s verse, producing a

figure of provocative physical presence. Celebrated in its own time for its “living skin,”

the painting derives its force from the tension between classical imitation and the

expression of individualized desire.42 The youth, a figure drawn from the street,

tramples the symbols of the arts, a gesture of inverted hierarchy and penetrating wit.

Classicism, for Caravaggio, is thus not stylistic stasis but method. It is the selection of

iconography and gestures from antiquity, the encoding of erotic and moral meaning in

a language legible to his humanist audience, and their transformation into an image

that fuses classical erudition with radical naturalism, grounded in his and his patrons’

mastery of textual and visual traditions and in his sustained practice of quotation.43

The two halves of Cupid’s arrows are differentiated, one of gold and the other of lead,

a detail that testifies to Caravaggio’s familiarity with classical sources in which the two

types of arrows signify amore e disamore.

44 As for Cupid’s black wings, these may have been inspired by Giulio Romano’s depiction of Cupid with dark eagle wings [fig.

40 Saslow, Pictures and Passions, 117.

41 Barkan, Transuming Passion, 113.

42 Saslow, Pictures and Passions, 115.

43 Langdon, Caravaggio: A Life, 215 .

44 Ibid., 215 .

8], encountered either through copies or in situ on palace ceilings in the Palazzo Te in

Mantua, within plausible travel range from Caravaggio’s home town. Black wings

signify impure love, insofar as visual tradition typically associates Cupid with white

wings. By breaking this convention, Caravaggio aligns the god of love with profane

Eros, thereby warning of love’s dangerous power.

Caravaggio’s atypical Cupid pose may also allude to Michelangelo’s Victory, extending

the theme of triumph and advancing a paragone claim in which painting outdoes

sculpture.45 At the same time, Amor Vincit Omnia crystallizes early seventeenth-

century naturalism: a living model, dramatic light, and an ironic gaze that drags myth

into the present, represent a high point where divine and earthly love collide.46 The

feather grazing Cupid’s inner thigh reprises an erotics of touch associated with

Donatello, intensifying the painting’s provocative charge.47

Caravaggio’s naturalism operates in two directions. One may say that the living model

comes first, and that myth is subsequently “dressed” upon it; this creates a volatile

tension between symbol and reality.48

The argument advanced here concerns not only a fusion between Cupid and

Ganymede, but also between Ganymede and Jupiter, articulated through a hybrid,

allusive, and legible conflation. Whereas ancient Roman images commonly represent

Jupiter seizing Ganymede in a forceful yet protective gesture [fig. 2], Caravaggio may

have sought to alter the traditional image of the abduction: his eagle grasps the youth

from behind. By altering Cupid’s wings to resemble those of an eagle and by quoting

the Ganymedean leg pose, the image of Ganymede takes prominence within the figure

of Cupid. “Impure love,” embodied by the profane Cupid, collides with the figure of the

abducted youth and with Jupiter, the desiring god who carries him off to Olympus. This

collision produces an interaction between the penetrative and the penetrated. In the

hybrid creature proposed here, the penetrated figure becomes desiring, no longer

helpless or passive, but smiling toward the viewer and responding to Jupiter’s desire

with desire of his own.

Viewing Amor Vincit Omnia through the classicizing mirror of Ganymede articulates a

hybrid and transcendent eroticism that exceeds the overt eroticism of Cupid’s splayed

45 Saslow, Pictures and Passions, 117.

46 Ibid., 214.

47 Saslow, Ganymede in the Renaissance, 183.

48 Langdon, Caravaggio: A Life, 218.

legs and genitalia. Caravaggio does not depict an innocent Cupid. The age of the

model and the feather’s contact with an erogenous zone reinforce the figure as a

deliberate convergence of Ganymede and Jupiter. Love triumphs as a bodily force that

collapses hierarchies: Cupid tramples the symbols of the arts, erases the divide

between the heavenly and the earthly, and merges the quotation of a Lysippus

sculpture with a living street model. In place of classical idealization emerges a

dangerous sexuality.49 Instead of Cupid’s traditional innocence and modesty, the

figure establishes direct eye contact with the viewer, activating erotic engagement.

This archetypal fusion combines the abducted youth beloved by a god, the desiring

god whose erotic impulses perpetually entangle him, and the double-faced god of love.

Through this tripartite fusion, Caravaggio transfers the erotic charge of the abduction

myth into a new visual field, one in which Cupid’s gaze is neither fearful nor victimized,

but smiling, conscious, and inviting. Desire is no longer a heavenly event entrusted to

Jupiter, but a human and physical force.

Caravaggio’s Baroque synthesis foregrounds emotion, naturalism, and chiaroscuro:

Cupid smirks, and the image turns desire into a warning. 50 As Cooper notes,

Caravaggio’s art is iconoclastic in its insistence on lived observation.51 In Amor Vincit

Omnia, the nude is not a spiritual ideal but a self-aware invitation to the homoerotic

gaze, and his realism is psychological as well as physical.

49 Ibid., 219.

50 Ibid., 219.

51 Cooper, The Sexual Perspective, 6.

Conclusion

The discussion of the myths of Cupid and Ganymede, their iconographic traditions,

and the conditions governing the representation of sexuality in the Renaissance and

Baroque sharpens the central research question: The hypothesis that Caravaggio

conceived Amor Vincit Omnia as a classicizing quotation in which Jupiter, as the eagle,

is condensed into the figure of Cupid, enabling a veiled signal of homosexual love and

a continuation of Ganymede imagery when direct representation was no longer

possible.

This study suggests that Cupid is constructed on a recognizable Ganymedean “type,”

serving as a vehicle for the hidden transmission of homoerotic and Neoplatonic

content to a connoisseur audience within the Giustiniani palace. Caravaggio was part

of a learned humanist patronage circle embedded in courtly culture, living within

aristocratic palaces, composing carnival poetry within male academies, and deeply

informed by Neoplatonic philosophy. Thus, he would have been well acquainted with

a conceptual framework in which eros functioned as a mediating force between bodily

and spiritual beauty. This framework furnished elite circles with a cultural language

that enabled the discussion of male desire and the figure of Ganymede within an

elevated symbolic system. In further evidence of this theory, a group of northern Italian

artists active shortly before Caravaggio likewise produced homoerotic works disguised

as mythology, reflecting freer modes of life prior to the Counter-Reformation.52

The iconographic anchor for the research question lies in the affinity between Eros

and Ganymede articulated by Roscher: the archetype of the divine youth mediating

between the human and the divine realms. Like Ganymede, Cupid bears a cup, serves

as Jupiter’s companion, and signifies divine grace and eternal youth.53

At the moment when Caravaggio was active, the social and moral restrictions on

homoerotic representation generated a private erotic field populated by youthful

models appearing as Bacchus or Cupid, androgynous musicians, and images that

flirted with a new, forceful, almost secular realism.54 In Amor Vincit Omnia, Caravaggio

appears to formulate a strategy for presenting homoerotic imagery through the fusion

of alla’antica style with sharp naturalism. His strategy includes a living body, poses

52 Saslow, Ganymede in the Renaissance, 199.

53 Wilhelm H. Roscher, ed., Ausführliches Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie, vol. 1

(Leipzig: B. G. Teubner, 1884–1890), 1654–56.

54 Saslow, Pictures and Passions, 115.

recalling ancient types, scattered symbols of culture and power subdued by love, and

the presentation of a youthful figure not as abstract theology but as a concrete Roman

present.

It may therefore be proposed that Amor Vincit Omnia functions as a critical case study

to comprehend the mechanisms by which homoeroticism was encoded in the late

Renaissance and Baroque periods. Through iconographic fusion, Caravaggio

rearticulates eros as a means of constructing a visual language in which male desire

could still be expressed within an increasingly suspicious world. In this context,

Caravaggio’s contribution to the Ganymedean tradition becomes clear: the fusion of

Cupid, Ganymede, and Jupiter is more than quotation, but sublimation, in which

Ganymede becomes Cupid and Cupid “bears” Jupiter upon his back. Erotic desire is

grounded in antiquity, yet realized in an original register endowed with new meanings.

Amor Vincit Omnia reveals the triumph of classicism and eclectic naturalism over the

constraints of its time.

Bibliography

Primary sources and translations

Cellini, Benvenuto. The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini. Translated by George Bull. London:

Penguin Books, 1998.

Hesiod. Theogony. Hebrew trans. Shlomo Shafan. Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 2008.

Homer. The Iliad. Hebrew trans. Shaul Tchernichovsky. Tel Aviv: Dvir, 1964.

Ovid. Metamorphoses. Hebrew trans. Shlomo Dykman. Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 1966.

Plato. Symposium. Hebrew trans. Shaul Tchernichovsky. Project Ben-Yehuda, 1929.

Vasari, Giorgio. Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Hebrew trans.

Moshe Barasch. Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 2021.

Secondary sources

Aurigemma, Maria Giulia. Il mondo di Vincenzo Giustiniani: Riflettere tra arte, cultura e natura Nella Roma del primo Seicento. Rome: Gangemi Editore, 2003.

Barkan, Leonard. Transuming Passion: Ganymede and the Erotics of Humanism. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1991.

Cooper, Emmanuel. The Sexual Perspective: Homosexuality and Art in the Last 100 Years in the West. London: Routledge, 1994.

De Groft, Aaron H. Caravaggio: Still Life with Fruit on a Stone Ledge. London: Giles, 2006.

Dover, K. J. Greek Homosexuality. London: Duckworth, 1978.

Hakanen, Ville. “Ganymede in the Art of Roman Campania: Ancient Roman Viewers’ Experience of

Erotic Mythological Art.” PhD diss., University of Helsinki, 2022.

Hibbard, Howard. Caravaggio. London: Thames and Hudson, 1983.

Langdon, Helen. Caravaggio: A Life. London: Chatto & Windus, 1998.

Langdon, Helen. Caravaggio and Cupid: Homage and Rivalry in Rome and Florence. London:

National Gallery Publications, 1998.

Murray, Jacqueline, and Nicholas Terpstra, eds. Sex, Gender and Sexuality in Renaissance Italy.

London and New York: Routledge, 2019.

Poseq, Avigdor W. G. “Caravaggio and the Antique.” Artibus et Historiae 11, no. 21 (1990): 147–167.

Roscher, Wilhelm Heinrich, ed. Ausführliches Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie.

Leipzig: B. G. Teubner, 1884–1937.

Saslow, James M. Ganymede in the Renaissance: Homosexuality in Art and Society. New Haven,

CT: Yale University Press, 1986.

Saslow, James M. Pictures and Passions: A History of Homosexuality in the Visual Arts. New York:

Viking, 1999.

Schütze, Sebastian. Caravaggio: The Complete Works. Cologne: Taschen, 2015.

Sichtermann, Hellmut. Ganymed: Mythos und Gestalt in der antiken Kunst. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1955.

Spike, John T. Caravaggio. New York: Abbeville Press, 2001.

[fig. 1] Amor Vincit Omnia (Love Conquers All), Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio,

1602, oil on canvas, 156 × 113 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, Germany.

[fig. 2] Ganymede Abducted by an Eagle, anonymous artisan, late 2nd century CE,

mosaic, Palace of Septimius Severus, Palatine Hill, Rome.

[fig. 3] The Abduction of Ganymede, anonymous artisan, 3rd century CE, mosaic,

dimensions and location unknown.

[fig. 4] The Rape of Ganymede, after Michelangelo Buonarroti, c. 1532–1533, black

chalk on brownish paper, 36.1 × 27.5 cm, Fogg Art Museum (Harvard Art Museums),

Cambridge, Massachusetts.

[fig. 5] The Musicians, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1597, oil on canvas, 92.1 ×

118.4 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

[fig. 6] Left: Omnia Vincit Amor, unknown artist, 1600, engraving, 21.6 × 15.8 cm, private

collection.

[fig. 7] Right: Eros Stringing His Bow, attributed to Lysippus, 4th century BCE, original in

bronze (lost), Roman marble copy after a Greek original, H. 123 cm, Capitoline Museums,

Rome.

[fig. 8] Cupid, Giulio Romano, 1528, oil on stucco, ceiling of the Room of Cupid and

Psyche, Palazzo Te, Mantua, Italy.